Coaching rugby using a Zone System

- David Weitz

- Defense

One of the hardest parts of a decentralized sport like rugby is keeping all players on the same page and working towards the same goal. One of the differences between rugby and American Football is that rugby has only very short periods between bursts of play.

During these breaks, the captain must establish an objective and get the team focused on completing tasks in order of priority. Find more rugby captain tips in last month’s piece about Navy SEAL leadership principles.

Creating and coaching a Zone System can help a rugby team understand objectives for each section of the field. By establishing the most pressing priority within each zone, a rugby coach can rest easy knowing that his/her players will be on the same page regarding their objective.

Another advantage of a zone system is that it allows the players and coaches to speak using the same language. The primary role of a Coach is to be a communicator who improves the team. If the Coach is using ambiguous terms s/he will find it difficult to communicate goals and have, the players understand the order or priorities. Miscommunication leads to frustration and tension between players and coaches which can be the downfall of any great team.

Labeling the Field

Creating a standardized way to speak about the field within your team is a fundamental component of having productive strategy conversations within your team. The best way to develop a standardized way to speak is by giving your team its own language. This process has the added effect of helping to develop and foster a unique team culture.

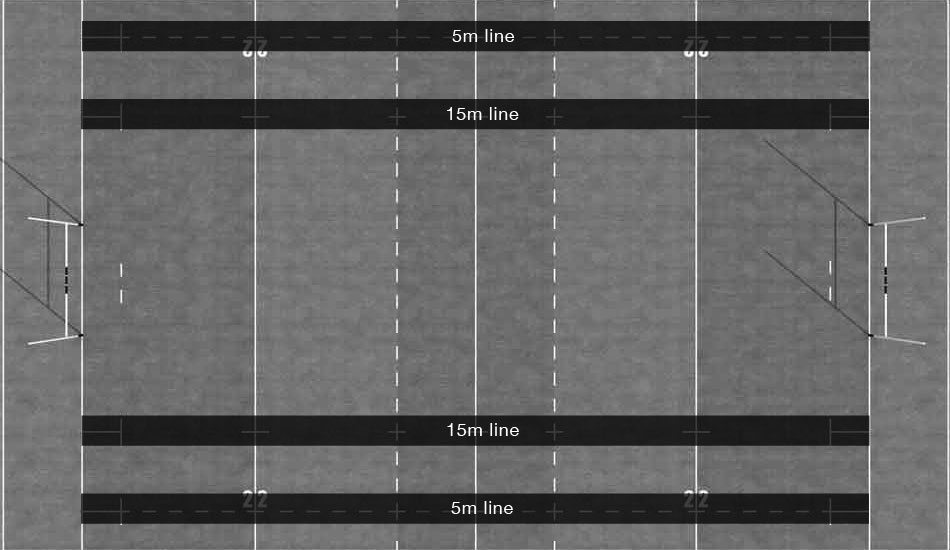

STANDARDIZE LINE NAMES

There are many different names for the areas within the field. While no one set of names is better than the other if you, as a team, are identifying things differently it will create frustration among players and coaches. Step one in creating a zone system is to define what you as a club will call each line. The names I use are the defending 5, defending 22, defending 10, halfway, attacking 10, attacking 22 and attacking 5. I have found these names pretty standard, but it’s important to make sure everyone on the team is using them to communicate with one another.

Here’s how it looks:

NAME YOUR CHANNELS

Developing continuity between the forwards and backs is incredibly difficult. Many times this is because the backs lack the language to describe where on the field a set move should finish. By being able to let the forwards know what channel the first ruck will be in, the loose forwards can tailor their line to arrive at the breakdown at the correct time. Over the course of a game, this saves the forwards and allows them to be more efficient. The diagram below is a simple way of identifying these areas. “Red, White and Blue” refer to a Kick while “U, S, A” refer to an attacking move. These are very basic and can be changed to suit your team and culture.

Here’s how it looks:

IDENTIFY THE TRAIN TRACKS

Another important area to identify is the “train tracks.” This is the area from the 5m to 15m lines that show the legal lineout zone. The train tracks are critical because they represent the widest playable area on the field. Any wider than the 5m line and there is a good chance that the ball carrier will be driven into touch, and the attacking team will need to compete for possession at the lineout.

Here’s how they look:

CREATING THE ZONE SYSTEM

The next stage of creating a language within your team is to label the different zones. I have always broken them down into four different zones with Zone 1 being closest to the defending try zone. Zone 1 goes from the try line to the defending 22m line. The primary goal in this Zone is to get the ball out of zone 1 to relieve pressure. From the defending 22m line to halfway is Zone 2. This Zone has a little more flexibility regarding where it ends which we will go into more detail below.

The primary objective of Zone 2 is to advance the ball into the opponent’s half of the field. Zone 3 is from the halfway line to the attacking 22m line. Zone 3 begins the attacking portion of the play. The goal in Zone 3 is to advance the ball into Zone 4. Depending on the strength of the team the strategy to do this can vary significantly. The final Zone is Zone 4. It runs from the attacking 22m line to the try zone. The only goal in Zone 4 is to score points.

Zone 1

Objective

Zone 1 is without a doubt the most dangerous and nerve racking Zone for any team. The number one objective of Zone 1 is to get the ball out of Zone 1. Preferably this is done by kicking the ball into touch, so the defending team doesn’t have to worry about a counter attack. Counter attacks can be especially troublesome in this area since the forwards will be focused on maintaining possession, not on filling the field with defenders. The ball is considered out of Zone 1 when a ruck is set outside of the defending 22m line. By setting a ruck outside of the defending 22m line, the attacking team can no longer kick the ball directly into touch and gain any ground.

Scrum

An attacking scrum in Zone 1 creates an opportunity where the attacking team is in a position to clear the ball and get play moved to a safer zone. The challenge from a scrum in Zone 1 is that the defense is expecting a kick to touch. This means they will have their loose forwards coming off of the scrum attempting to pressure the kicker. Another consideration is that the backs receiving the kick are positioned to counter-attack. If the kick does not reach touch or provides the opportunity for a quick lineout, expect the receiving team to be hot on attack. As a result, there is no room for error for the team looking to clear the ball out of Zone 1.

One way to give your kicker time is to run a crash phase from the scrum. The specific move should play to the strength of the team but many times this is either an 8-man pick or a crash ball from 12. Stress with your captain and players that the goal of this move is not to break tackles. Instead, you want your ball carrier and supporting players to set a clean ruck that allows an easy pass from the halfback to the kicker.

Another option best used when several defenders are rushing the primary kicker is shown below. In this move the next best kicker lines up inside of the fly-half (directly behind the scrum). When 10 gets the ball, he can then pass it to the man lined up behind the scrum. The angle of this move makes it very hard for the loose forwards looking to charge down the kick to change direction and apply pressure. The danger here is that a loose forward who stays on an effective flanker running line will be in excellent position to charge down the kick if they can identify the second kicking option.

Lineout

From a lineout, the objective within Zone 1 remains the same, get the ball safely to touch. But first, you need to get the ball. A lineout is far from guaranteed possession. In Zone 1, the opposition doesn’t need to worry about their try line, so they’re free to contest in the air. This lineout call needs to be a high percentage choice, preferably with the smallest possible margin of error.

One factor to consider is which direction your scrum half passes best. In a perfect world, your scrumhalf will pass equally well with both hands. In reality, most ruggers will have a preference for one hand over the other. Since the majority of rugby players are right handed, this article assumes that your scrumhalf is as well. If you’re a lefty, simply do the opposite of what we’re outlining here.

The general rule of right vs. left side lineout play is that you want to help a scrum half who is throwing from their weak hand (towards their dominate hand). The simplest way to accomplish this is to limit the distance that the scrum half must pass the ball, by throwing the ball towards the back of the lineout. The second is to give them a little momentum when passing with their non-dominant hand, by dropping the ball off the top of the lineout to the scrum-half who is already moving towards the fly-half.

When thinking about executing a clearance kick from a lineout, the opposition fly-half is not an immediate concern since they must start 10m away from the first receiver. From most lineouts, the “gunner” (defender at the back of the lineout who breaks directly for the first receiver) or scrumhalf will typically apply the most pressure to the first receiver. As with scrums, performing an action to keep these defenders occupied can be an effective way to buy your kicker time. The primary goal of the crash ball is not to gain ground but to attract defenders and provide clean ball for the scrumhalf to pass to the kicker.

Another option for creating space and time for an exit kick is to set up a maul from the lineout. With this maul, you are not looking to gain ground. Instead, the forwards want to ensure the ball gets back to the scrum-half and delays the “gunner” and scrumhalf. When the ball is cleared and kicked by the fly-half, the wing on the near side will chase to put the forwards onside. Once the forwards are put onside they will occupy the train tracks and rely on the open-side flanker linking the forward line with the backs to nullify any counterattack.

Zone 2

Objective

Zone 2 is a transition zone. For territorial reasons, it is unlikely that your team will score from a phase which begins in Zone 2. Therefore, the objective in Zone 2 is to get your opposition out of scoring position and into a position where you have the opportunity to score points. Kicking the ball to space, specifically, the train tracks that are discussed in the first section, is one of the best ways to achieve this.

Zone 2 runs from the defensive 22m line to the halfway line. If you have a strong kick and chase game, Zone 2 can be very strong for your team. As such, you may want to extend it all the way to the attacking 10m line. If your kick and chase game are weak, you may want to shrink this Zone to the defensive 10m line. One approach which is a little more flexible is to say that Zone 2 is the area where a penalty against your team might result in a kick at goal for the opposition. To modify Zone 2, your team’s decision makers will need to have a good idea about the range of the kicker you are facing and be able to communicate this to the rest of the team.

General attitude and play in Zone 2 can be tricky. On one hand you are still in your half and have the pressure of a mistake leading to the opponent having an attempt at a penalty goal or moving the ball into Zone 1. On the other hand, you are out of immediate pressure so you can have a few more opportunities to use your possession and attack.

In Zone 2, many teams who don’t use a Zone System will find it difficult to strike a balance between kicking away possession and attacking with the ball in hand. It’s important the team’s playmakers evaluate the situation in front of them and make a decision that fulfills the objective of the Zone. Remember, the objective within Zone 2 is to get the ball into the opponent’s half. As a result, the first receiver will be looking for opportunities to put the ball on the train tracks and allow for a good chase.

Scrum

One of the most efficient ways to do this off of a scrum is by having a crash runner coming from the backline. Who this is can vary from team to team. The idea is to give the fly-half two options: kick if there is space or use a crash runner to set a ruck close to the scrum where support can come from the loose forwards. When setting up this move the three remaining backs who are not running the crash line should align themselves flatter than normal so they can get a good start to their chase. If the fly-half determines that a kick would result in a counter attack, they will give the ball to the crash runner rather than kick. The open-side flanker and number 8 are responsible for securing the ball at this ruck. The fly-half should stay out of the ruck to ensure they are in the position to make a tactical decision on the next phase. Again, either kick to space or play another crash ball.

Lineout

Lineouts in Zone 2 are difficult for kickers. In this zone it’s easy for the defense to keep their blind-side wing deep in the backfield at a lineout because they know they will get good pressure from the gunner and scrum half on the attacking team’s first receiver. This pressure on the fly-half coming from the lineout allows the remaining backs to push out and cover the opposition’s blind-side wing when they insert into the backline. Similar to Zone 1, establishing something to prevent the opposition’s loose forwards from charging down the kick is a priority.

In Zone 2 the same methods for preventing pressure can be applied. One added option is to go with a shortened lineout and use the spare forward pod which threatens to crash on the first phase. Shortened lineouts have a couple of effects on the defense. The first and most obvious is that the defense is more likely to honor the threat of a running attack. This threat can cause defenders to over-commit to the run instead of preparing to counterattack from a kick.

An added benefit of the short lineout is that the opposition’s loose forwards (typically some of the best defenders on the team and the most likely to spoil or steal ruck ball) will be back 10m from the lineout. With slower players remaining in the lineout, your fly-half may have slightly more time than usual to get a kick away.

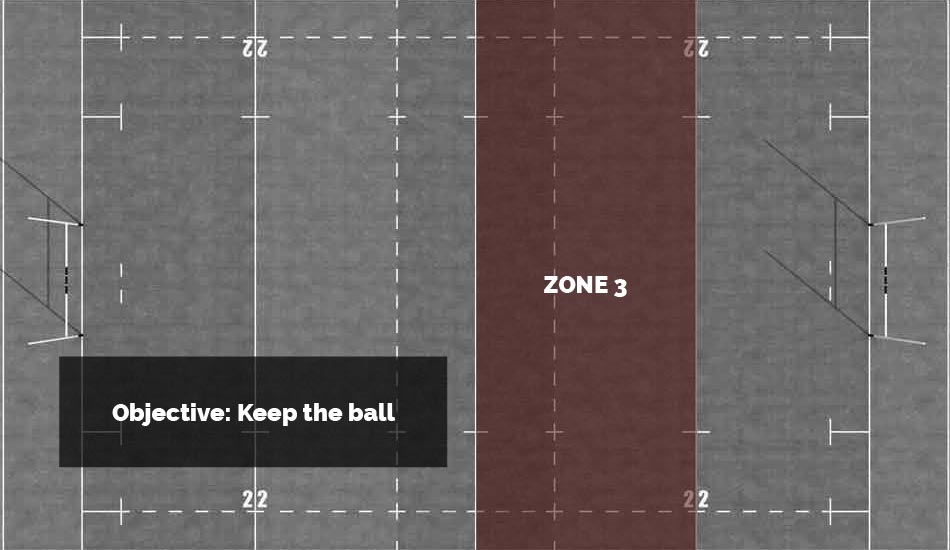

Zone 3

Objective

Zone 3 is the best area of the rugby field for your team to develop pressure, stress the defense and cause them to exert energy. In Zone 3, the objective is to keep the ball in hand and impose your team’s will on the defense. Your team’s particular strengths will determine your attacking structure. But being effective in Zone 3 requires multi-phase play and should be used to wear out the opposition. Keep the ball. Keep the ball! KEEP THE BALL!

Similar to Zone 2 the exact definition of the start of Zone 3 can vary from team to team. The standard to work from is that Zone 3 starts at the halfway line and ends at the attacking 22m line. If you team decides to change Zone 2’s dimensions, Zone 3 will need to change accordingly. For example, if your team has a quality, tactical kicker and you have made the choice to extend Zone 2 to the attacking 10m line than Zone 3 wouldn’t start until the attacking 10m line. If your team is good at developing continuity between phases but has poor kick chase Zone 3 might start at the defending 10m line.

Scrum

The attacking options from the scrum are unlimited. In Zone 3 the goal is to get the ball moving forward and continue to move it forward beyond the attacking 22m line. The number one thing to think about is working through team strengths in Zone 3. It is very rare that a solo try will come from this Zone against a quality team. Instead, any line breaks will have to be supported, and the attacking player must be able to use his support to finish off the move.

Lineout

Lineout options are abundant in Zone 3 of the rugby field. If your team has strong forward runners, this is a chance to get them running out wide and attacking smaller defenders. If your forwards are better suited to mauling, keep the ball tight and compress the opposition’s defensive line. Again, the chance of a Try coming from the maul in Zone 3 is pretty small. But mauling can be an effective way of gaining ground and forcing a penalty. Zone 3 is all about using the strength of the team to put pressure on the defense. Few strategies achieve this better than a well-executed maul. The maul in Zone 3 is especially effective since the opposition doesn’t necessarily know that it is coming so it has not set up its defense to counter it.

Zone 4

Objective

The final piece of the field is Zone 4. In Zone 4 everything else falls away and the only objective is to score points. The team has worked to get into Zone 4 and must be able to convert the field position into points. While Zone 3 develops physical pressure on the defending team, Zone 4 puts psychological pressure on them which can result in mistakes and scoring chances. When the opportunity arises, give your team’s goal kicker the opportunity to put points on the board in Zone 4. If a team is able to leave Zone 4 with points 75% of the time, the chances are very good that they will come away with the win.

Scrum

Scrums in Zone 4 present an opportunity for the backs to convert first-phase possession into a Try. In Zone 4, a single line-break can result in a Try. This makes it an excellent area to use the best runner and put him into space. Back Row moves off the scrum can also be very useful tools, especially if they are attacking the short side of the field. Just like previous Zones, it’s important to play to the individual strength of the team. Zone 4 is where you want to get the ball in the hands of your playmakers and give them the confidence to attack.

Lineout

A lineout in Zone 4 gives your team a premium chance to generate points. Whether the strength is the forward pack’s ability to rumble or the backs’ being able to put a playmaker in space. A lineout in Zone 4 can give your team a chance to highlight whatever your strength is.

Many forward packs employ mauls and lineout moves to shoot for a Try in Zone 4. The maul, executed correctly, is a near-unstoppable tool close to the line. Mostly because it draws in so many defenders that it can also become a decoy maneuver. If a team demonstrates mauling dominance early in the game, the opposition will be on alert for the maul. With defenders focused on stopping the drive, a sneaky front or back peel can be a great weapon. Because these kinds of moves are designed to score points, use them sparingly and only inside Zone 4 as they’ll be less effective if the line isn’t close.