10 stupid-simple recovery tips for rugby

- Tim Howard

- Diet, Flexibility, Recovery

The game is over. The fight is done for now. The coordinated brutality of the match has reached its end point. You left absolutely every ounce of your being out on the rugby field.

Odds are, you’re going to spend the next couple days feeling pretty beat up. Rugby games, regardless of the sheer amount of physical contact, has a tendency to draw out extreme and prolonged soreness.

If these acute areas of discomfort are not properly tended to, they can lead to longer-term overuse / repeated movement injuries that may require time off and a trip to a physiotherapist.

Like rugby practices and off-field strength and conditioning training, recovery needs its own series of modalities and own structured plan.

Putting actual effort into recovery will significantly reduce the amount of time you feel like crap, decrease the time you can’t train due to niggling injuries, and increase the amount of quality rugby practice you can get in. The goal of this article is to be a reference guide for several different forms of active recovery work for rugby players.

1. RICE Versus MEAT

RICE stands for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation. This is the typical advice from most medical professionals regarding treatment for the aftermath of acute stress response to hard training or rugby games. The issue here is that doctors aren’t used to working with people that want to stay active and want to return to some physical activity as soon as possible. RICE is a prime example of a medical professional taking a conservative approach to physical therapy. RICE is entirely appropriate if you’re actually injured playing rugby. But, immobilization is definitely not the best course of action for less severe problems. Don’t worry ruggers, there is a much better option:

MEAT Therapy. MEAT is an acronym for Movement, Exercise, Analgesia, and Treatment. The next nine points on this list will explain how to apply MEAT principles to manage recovery during the rugby season. To break each aspect down a little further:

Movement: Small bodyweight movements are known to decrease swelling, edema, and pain to specific areas. In regards to acute injury, our nervous system is very efficient at dealing with pain tolerance when movement is introduced. Have you ever had some kind of issue with prolonged soreness/ache that got better once you warmed up properly and performed some movement in that area? Assuming there isn’t traumatic injury resulting in some catastrophic structural problems, our bodies tend to either process pain or initiate movement. Thus moving more will often help with pain management of smaller acute problems.

As far as fluid management, movement requires muscles to contract. Even a small contraction pushes fluid throughout the lymphatic system (which uses the hydrostatic pressure of concentric muscle action to push excess fluid out of an area). This is why tens/stim units are used extensively in physical therapy and to treat rugby injuries. It initiates contractions to push fluid out of areas we don’t want extra fluid pooling. Another benefit of small, unloaded movement is that it does not require a high amount of stress to signal the healing processes for ligament repair. Small movements can, therefore, promote healing acute painful injuries while reducing the pain felt as well.

Exercise: As opposed to movement alone, exercise requires an external load. The obvious benefits here are the muscle strengthening aspects of resistance training. External load also signals the initiation of new bone formation. When a bone senses load/stress, it responds by preparing itself for the next time it will be exposed to it. The higher force production required to move external resistance also produces an even bigger lymphatic “pumping and flushing” effect.

Exercise is much better than movement alone for improving and problems with the elastic properties of muscles. A rugby player’s muscle fibers should be taught but pliable. Properly directed exercise can help break up adhesions and trigger points and reduce areas that experience over-active nervous activity (muscles so tight, they almost feel like bones).

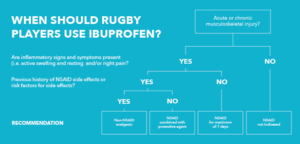

Analgesia: This step is super-easy. It pretty much only involves dousing your body’s trouble spots in Icy Hot and just forgetting about it. Some over the counter NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, like ibuprofen) appear to do more harm than good for athletes trying to recover. Sure, you feel better short term, but what you don’t feel is the interruption of our normal healing and inflammation responses when NSAIDs are introduced. Topical analgesics still have pain-relieving properties and may help augment all of the other benefits mentioned with movement as well.

Treatment: This aspect is so broad that it is hard to fit the definition in its entirety into one article. Points two through nine are going to go into some of the available treatment options.

Compression Materials

This is as easy as putting on a shirt or a pair of pants. Luckily, we live in a time where numerous companies have developed rugby-specific recovery/compression clothing. Some research suggests that tight enough clothing can reduce swelling on a cellular level and promote the movement of waste products out of overworked muscles.

Also, compression material worn during training and practice may actually improve performance due to higher proprioceptive awareness (your ability to know where your body is and how it is moving in a given space) and by adding in extra joint support.

Honestly, research is still a little inconsistent here, but, the way I look at it, if something as easy as putting a tight pair of pants on is helping me recover even 1% faster, then I am going to utilize it. For utilizing compression material for recovery purposes, you just want to put it on immediately after games/hard training and wear it for 24 straight hours.

Flossing

I know what you’re thinking. “How on Earth will keeping my teeth clean help my recovery?” I am not talking about that kind of flossing. I am talking about using something similar to a tourniquet to tack down a certain area of soft tissue then go through a series of movements to “floss” the tissues through the compressed area.

This is an excellent way to perform a very specific movement while keeping pressure directly on a trigger point or an adhesion area. Keep in mind for this and every other soft tissue modality listed: It takes about two minutes of active work to produce any kind of meaningful change in soft tissue quality. So, when flossing or doing anything else, you must spend at least two minutes working each area.

An excellent resource for flossing info is Kelly Starrett of MobilityWOD fame:

Soft Tissue Work with Massage Ball

Very similar to flossing, using a rehab massage ball to dig out a sticky area is fantastic for improving overall tissue quality. The small surface area in contact with the ball allows for work to be done in very specific places. Fair warning, this is not enjoyable while you do it. You will feel immediate improvement once you get done rolling everything out. Some popular areas to dig into includes the arch of your foot, your IT/TFL/piriformis area, the entire thoracic/cervical aspects of your spine and back.

Also, when standing, a firm massage ball is great for getting into trouble spots in the chest and deltoids. Just pick a spot that feels tight or tender and dig for about 2mins. This is best when you pick 2-3 areas a day to work on 2-3 times per day until tissue quality improves (pain decreases, pliability is restored, movement improves, etc.).

Mini Workout

The mini workout is an unusual recovery concept. Hopefully, if you take your training and sport seriously enough to take the time to read this article, you also take it seriously enough to have a structured warm-up and cool-down protocol. The mini workout just involves a 15-20 minute workout only consisting of a warm-up and a cool-down. If you have any lagging/weak areas, this is a great time to focus on those. For example, if your core is weak, you could warm-up, perform 2-3 sets of plank variations and some supermans, cool-down, and call it a practice.

This definitely fits under the Movement and Exercise categories of MEAT Therapy. All of the above-mentioned benefits of those two principles apply here as well. Since this does take a little time, mini workouts 2-3 times a week and about 12-24 hours after games or hard training should be sufficient.

Return To Parasympathetic Dominance

This is going to be one of the most complicated aspects of this article. Athletes involved in intense sports like rugby sometimes have a hard time “turning it off.” The focus felt in competitive rugby, when boiled down to its most primordial biological level, is basically just a fight or flight response. In other words, this is a state of sympathetic nervous system dominance. This is our hard-wired natural defense mechanism our ancestors used to assess emergency situations (like, whether to fight the grizzly bear or run away from it).

Being able to tap into this system is not a bad thing, and we do it on accident sometimes without even realizing. The near brush car accident or even watching an enthralling game can cause your heart to start beating a little bit faster. The issue with sympathetic dominance is that it is exhausting. Also, being too sympathetically driven can cause numerous issue with muscle tissue quality. Being too “on” can cause unwanted high frequencies of muscle contraction that are just the result of an overactive nervous system blasting impulses to certain areas.

Some athletes are better than others at making the shift from that fight or flight level to the parasympathetic “feed and breed” state. Luckily, it is pretty easy to tone down those sympathetic messages. Something as simple as 12-20 minutes of moderate intensity (heart rate at 65% to 75% of max) aerobic work can cause a shift in dominance. This is best done immediately after games and/or hard training.

Hydrotherapy: Ice Baths

Unfortunately, there is a ton of conflicting evidence out there for ice baths. That doesn’t mean they don’t serve a purpose in a structured recovery protocol. To sum up a ton of research out there, ice baths immediately before or after intense physical work either limits performance or inhibits recovery processes. So, we do not want to take an ice bath at either of those times.

The limited research where ice baths were done up to 8-12 hours before or after intense physical work, participants self reported soreness was down, self reported motivation to return to activity was higher, and sleep quality improved. Even though the actual biological improvements are still pretty inconsistent in the research, the psychological improvements associated with ice baths are too consistent to be ignored. These are best when performed 1-2 times a week, as needed, several hours after those hard rugby games.

A 2013 research project conducted by Higgins, Cameron, and Climstein at the Australian Catholic University into the effects of hydrotherapy after a simulated rugby game determined that “rugby union players aiming to attenuate the effects of DOMS postgames is to take 2 × 5-minute CWIs baths immediately after the game.”

Hydrotherapy: Contrast Showers

Ok. This one is going to be a little weird. Yes. I am going to tell you how to perform a “power shower.” Contrast showers involve using hot and cold water in alternating intervals to elicit a “pump” at the capillary/cellular level. This helps on two different levels of recovery. The “pump” effect of dramatic changes in temperature helps to create mobility in inter/intracellular fluid. The second is that studies have shown that contrast showers improve mood and improve perceived readiness to compete/train hard again. Contrast showers should be performed for around 20 minutes of 45 seconds hot, 15 seconds cold. Always end on cold.

Joint Support

examine.com is an excellent, unbiased resource for supplement research and review. After digging through the droves of peer-reviewed studies available, they came up with this list for proven to work joint health supplements:

Glucosamine – The sulfate (not hydrochloride) version has been proven to help with osteoarthritic knee joint pain in positive responders. Unfortunately, about half of all people are going to be non-responders. They suggest 500mg three times a day for a total of 1,500mg daily.

Curcumin – Is a component of turmeric and has anti-inflammatory properties similar to over the counter NSAIDS. Start with 200mg twice a day with food. If pain persists, the dose can be bumped up to 500mg for a daily total of 1,000mg. Also, it seems like curcumin works synergistically with piperine (a compound in black pepper). Adding 20mg of piperine with each dose seems to be beneficial.

Boswellia Serrata – Not only has this been shown to reduce join pain, it has also been noted as actually improving joint flexibility in some cases. Examine recommends taking 1,800mg of crude oleoresin three times a day. If you’re like me, and the thought of chewing on a plant used to synthesize turpentine is a little off-putting, you can always look for products like 5-Loxin and Aflapin

. For either of those, 100-250mg once a day with food is all that’s needed. It can also be found in products like Animal Flex

and other joint support complexes.

Fish Oil – Being one of the most studied supplements on the market, there is an unbelievable amount of evidence supporting fish oil’s ability to relieve joint pain not associated with osteoarthritis. It’s effective in treating joint-related work pain, it has immunosuppressive properties that make it a useful option for people with rheumatoid arthritis, and higher doses can help with training related joint issues. Fish oil should be taken with a meal and up to 2,500mg can be used by rugby players.

Chondroitin – Also improving joint pain and mobility, chondroitin is typically taken with glucosamine (even though more research is needed to determine if they have a synergistic effect). The only contraindication is that chondroitin is also a powerful anticoagulant. So, people on blood thinners or blood pressure meds need to be very cautious when taking this supplement. 200 to 400mg three times a day is recommended.

Vitamin C – Success in treating complex regional pain syndrome (an incredibly painful chronic joint disease) and its importance in collagen formation make this a must for this list. It’s recommended dose is 500mg a day.

Get Your Head Right

I strongly suggest every athlete that takes training and sport seriously take the time to work on their mental game as well. Although there are tons of books available that discuss the psychology of sports performance I recommend everyone seek out Psych by Dr. Judd Biasiotto. Not only does he have a doctorate in psychology and is one of the most sought after sports psychologists in the world, but he was also an incredibly successful athlete himself. Taken from his website:

“In addition to his professional achievements, Dr. Biasiotto also has the rare distinction of being a world-class powerlifter and bodybuilder. He has set 101 state records, 47 region records, 32 American records, 16 national records, and 14 world records. In 1987, Powerlifting USA ranked Dr. Biasiotto as the fourth best powerlifter of all time. In the year 2000, he was named as one of the top fifty lifters of the millennium by Powerlifting USA. That same year Dr. Biasiotto became the oldest man to win the national and world open bodybuilding championships.

His best lifts at a bodyweight of 132 pounds was a bench press of 331 pounds and deadlift of 551 pounds. In 1987 he shocked the sports world by squatting a mind boggling 603 pounds. That lift which exceeded the previous world record by over 80 pounds is considered one of the greatest feats of strength in the history of powerlifting.”

Have you personally found anything on this list to be helpful? Are you going to try something out? Let us know in the comment section below!